INTRODUCTION

Lance Armstrong, a professional road cyclist, confessed to using performance-enhancing drugs on the renowned American talk programme with Opera Winfrey in 2013. Understanding what is permitted and prohibited in athletics has somehow spread to every home. People began to read about doping, which raised awareness of prohibited substances at amateur sports. The context in this case is how the biker got so forthright about his drug use without even considering the consequences. Eventually, after the reports were made public, the cyclist renounced all of his honours. And it ushered in a period when the world anti-doping agency began to keep an eye on sports regulatory bodies, athletes, and coaches. Following this, WADA banned a few nations in 2016, including the Russian Rio laboratory[1]. In 2014, India was the source of reports of sports corruption, and individuals were being held in jail or faced expulsion. Suresh Kalmadi, an Indian Politician and former President of Indian Olympic Association went under scrutiny due to the allegation of corruption in the 2010 Commonwealth Games which was held in Delhi. The CBI investigated in the matter and Delhi High Court formed an independent committee for the investigation on the charges of criminal conspiracy (Section 120 B) and cheating (Section 420) of Indian Penal code[2]. Suresh Kalmadi had to spent 10 months in jail following the restraint from attending the opening ceremony of London Olympics 2012[3]. The previous ten years were a turning point in the development of sports law in the general legal practice and established important precedents. The importance of sports law was recognised by the courts in developing nations like India, where a need for specialists with expertise in sports-specific law was beginning to emerge.

However, the commercialization of sports and the sports industry was always on par in developed nations like the USA and the UK. Sports are ingrained in English culture and have a significant economic impact on the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom is far advanced in terms of comprehending sports legislation and its requirements due to the influence of an already prevalent sports culture.

The first question one must always address when discussing the legal aspects of sports is “sports law or law in the sports.” So, is there a sports law or does that just refer to a term used by lawyers?

In this article the author discusses about the history and development of sports law to concrete the fact if the specific legal sub discipline of sports law exists. Along with this the author explains the practical utility of sports law through legal authorities and instances of sports law from the various jurisdictions.

HISTORY OF SPORTS LAW

That was in the early 1950s, when tax issues were occurring in the two major sports of cricket and football. The discretionary clause from the employment contracts of the Football League Regulations that permitted payment of a benefit from a professional footballer’s employment contract was then eliminated with the approval and amicable decision of the Association Football Players and Trainers Union (now known as the Professional Footballers Association). The ratio of the decision was based upon the 1927 ruling of House of Lord in Seymour v Reeds [1927] AC 554 [5]. It revolves on the fact that, inadvertently, the law in the sports business was evolving slowly and steadily at its course [6].

Development of Lex Sportiva

Term lex-sportiva was claimed to be originated by Matthieu Reeb, the acting Secretary General of the Court of Arbitration for Sport. It is during the time of publication of the first digest of the Court of Arbitration of Sports’s judgments on the sports during the period of 1986 to 1998. It was reiterated that the term was first coined by the president of the IASL, Michael Stathospolus during the 5th IASL Congress on Sports and European Community Law where Matthieu Reeb was one of the speakers [7].

The CAS has rendered significant decisions in sports-related cases over the past 38 years, including those involving doping, contractual disputes, organisational disputes, and judicial reviews of decisions made by sports governing bodies, such as those involving football transfers and compensation issues. The sports governing bodies refer specialized instances to CAS for examination, such as Oscar Pistorius, a South African amputee athlete, in order to determine his eligibility to compete in the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing [8].

Ken Foster asserts that the decisions and recommendations of the Court of Arbitration for Sports are forming a Lex Sportiva, or body of legal precedent, for the practise of sports law. In the case of Norwegian Olympic Committee and Confederation of Sports v. International Olympic Committee (CAS 2002/O/372) the categorization became more clearly apparent. The CAS used the sports codes of the governing organisations in this dispute as its legislative basis. The Olympic Charter, Swiss Procedural Law, and CAS doping jurisprudence were the three primary legal sources [9].

Many sports law ideas, like the principles of strict liability (in doping cases) and fairness, have been significantly developed and refined by CAS jurisprudence and may be considered to be a component of a growing “Lex Sportiva”. Since various sport regulations form the foundation of CAS jurisprudence, the parties’ reliance on CAS pleadings amounts to their selection of that particular precedents in case law, which incorporates certain general principles derived from and applicable to sports regulations [10].

The Norwegian award’s terminology points to the concept of lex sportiva having a narrow and specialized use. Because they are “generic ideas developed from sports regulations,” the principles discussed here can be applied to any sports activity. This suggests that the lex sportiva essentially consists of the correct application and interpretation of the federations’ legislation. The fact that it derives from the constitutional structure that sports federations established to administer sport makes it a lex specialis that is applicable to the administration of international sport.

Prof. Ken discusses the jurisprudence of the court of arbitration for sports in his publication using the following key principles i.e,

Lex Ludica – The subjects of sporting disciplines and the internal rules of the sports.

Good Governance – The principles underlying ultra vires. The authorities must make decisions according to the required standard.

Procedural Fairness – Sports federations are required to adhere to minimal administrative requirements as part of disciplinary actions.

Harmonisation of Standards – Standards should be balanced and consistent, emphasizing that all federations should be subject to the general guidelines established by the CAS.

Fairness and equitable treatment – It outlines the proportionality of penalties and the repudiation of automatically imposed punishments. It establishes estoppel and genuine expectation according to CAS jurisprudence.

LEX SPORTIVA AND LEX MERCATORIA

Through centuries of custom and judicial practice, Lex Mercatoria, or the law of merchants, was formed in the context of international commercial law and arbitration law. Both public and private law recognise Lex Mercatoria as authoritative. When compared to Lex Sportiva, the CAS relies on the less number of judgments and awards passed by the CAS but its impact on the dispute resolution and judicial review in sports is efficient and consistent to grow Lex Sportiva into a substantial source of Sports Law. However, Lex Sportiva is restricted to the CAS cases that serve as the cornerstone of International Sports Law, making it applicable to a wide spectrum of the International Sports Industry including its stakeholders [11].

DEVELOPMENT OF SPORTS LAW PRACTISE AND ITS PRACTICAL UTILITY

Initially, the topic of whether to refer to this argument as “sports law” or “sports and the law” sparked concerns about the relevance of sports law. If there is a sports law or if it concerns the law in the sports industry. The precedent and supporting evidence for the applicability of sports law, however, were being established through the literature, academic papers, books, and pertinent judgments in the context of sports. In his article, Simon Boyes categorised sports law into four categories based on location and legal activity, i.e., domestic, national, regional, and international elements [12].

The sources of sports law can be found in the earlier writings of writers, scholars, professionals, and legal precedents. The 1988 version of Edward Greyson’s book, known as the father of sports law, was the first to use the phrase “sports law” and to describe how it applied to athletes including jockeys, cricket players, and football players. The presence of sports law was examined in the book in relation to problems brought on by violence, drugs, commercial exploitation, and political infraction. Therefore, the approach to sports law was constrained and obscure even in the third version of the book.

As mentioned above, Ken Foster’s journal critically analysed the title “Lex Sportiva” and the fundamentals of sports law. A major factor in the development of sports law in the field of international sports law is the

academic literature and periodicals.

The author here describes the sources of sports law from the point of views inspired by the categories mentioned by the author Simon Boyes in his article.

| CATEGORY | AUTHORITY | LEGISLATION |

| Local/State/Region | Sports Governing Bodies, State Authorities and their disciplinary committee | Rules of sports governing bodies, internal rules and regulations. |

| Domestic/National | National Sports Governing Bodies, Court of Arbitration for Sports, Civil Courts or Criminal Courts as per the case context | Rules of national sports governing bodies, case specific legislation such as contract, employment, defamation, tort, human rights, |

| International | International Sports, Governing Bodies, Courts of Arbitration for Sports, Civil or Criminal courts as per the case context |

Sports Governing Bodies

Disputes around the sports law are majorly governed by the sports governing bodies such as Archery GB, British Swimming, UK athletics, British Basketball, Badminton England, Ice Hockey UK, Rugby Football League, British American Football Association are few of the examples of national governing bodies for the sports in theUK [13].

There is a specific code of practice for sports governing bodies issued by UK Home Office which mentions the role of governing bodies, general principles to keep accountability on the licenses and endorsements in order to ensure best interest of sports and sports persons in England [14].

Additionally, the Football Association, which has its London headquarters at Wembley Stadium, is the governing body in charge of overseeing association football in England. At the national level, the FA is in charge of both amateur and professional football. All English professional football teams are the members of FA and the FA has veto power over club rules and executive level appointments.

These sports governing bodies has jurisdiction and rules to regulate their specific sport. If any issue related to sportsperson, eligibility or any kind arises then the sports governing bodies has powers to resolve the issue and provide sanctions related to that. Also, it was the contention that the relationship between the sports governing bodies and sportsperson is contractual in nature that there is no availability of judicial review in such decision. However, according to the past few awards of the CAS, there are cases of judicial reviews heard by the Court of Arbitration when the matter had elements of public policy and interest. There is a grey area of judicial review which exists besides the contentions made by the academicians and professional in the past that the nature of the relationship is contractual. For instance, when the athletes were imposed of ban and lifetime ban, it was one of the most controversial debate.

The cases of Flaherty v. National Greyhound Racing Club [15], Mcinnes v. Onslow-Fane [16] and Enderby Town Football Club v. Football Association [17], In which the courts ruled that because sports governing bodies operate as a private organisations under a contract with the claimant/sportspersons, judicial review is not a remedy to the sanctions. According to the observation of precedents, it may be concluded that the contractual relationship between the Sports Governing Bodies and the sportspersons make English Courts reluctant to get involved in athletic disputes. Judicial Review is not an option in issues involving athletes.

The courts are not allowed to interfere with “Sports Governing Bodies” judgments, even though judicial review merely serves to determine whether the decision-making process was actually legitimate. One could argue that using judicial review as a tool to improve erroneous public law processes is helpful. All attempts to raise judicial review of sports disputes were rejected by the courts in R. Mullins v. Appeal Board of the Jockey Club [18]. The Willie Mullins racehorse “Be My Royal” tested positive for significant levels of morphine in his urine. Despite the acknowledgment that the morphine might be harmless due to food

contamination. Nevertheless, “be my Royal” was disqualified by the Jockey club’s disciplinary committee for breaking rule 53. The decision was upheld notwithstanding Mr. Mullins’ appeal to the Jockey Club appellate board. Additionally, the courts upheld the decisions made by the court of appeal in R v Disciplinary Committee of the Jockey Club, ex p. Aga Khan, concluding that Stanley Burnton J.’s conclusions in the State Proceeding were primarily of a procedural nature.

Irrespective of the lack of judicial review, it is accurate to say that developments have been made in the assessment of the procedures sports governing organisations employ to make judgments. After Bradley v. Jockey Club [19] established a private law “supervisory jurisdiction” over the governing body, which was later held to extend to all matters of “importance,” Lord Denning’s decision in Nagle v. Feilden [20] stated that “Organizations holding predominate power over a particular area would come under the court’s jurisdiction as a matter of public policy.”

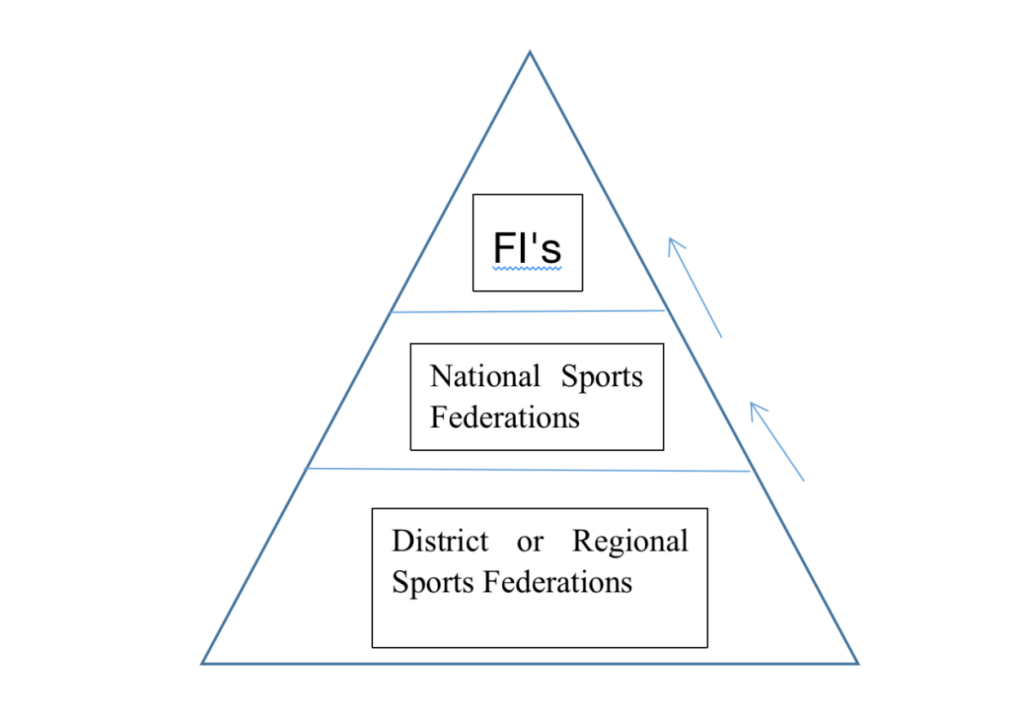

The International Federations

International Federations maintains the conduct and regulate the standards of the sports competition on the international level. These federations are recognized by the International Olympic Committee on the parameters of the Olympic Charter. Without the recognition of the International Olympic Committee these federations cannot participate in the Olympic Games or any other associated competition [21]. The hierarchy of Sports Federations from district to international level is described below.

The Indian Olympic Association was suspended by the International Olympic Committee in 2012, which prevented India from competing in the Olympics and barred any individual Indian athletes from competing under the Indian flag. The Indian Olympic Association was suspended by the IOC for failing to uphold the Olympic Charter’s rules and for appointing politicians with a history of criminal conduct to the IOA’s administrative positions. However, the IOC issued a statement in 2014 removing the suspension and re-establishing the committee [22].

The governing boards and regulatory bodies operate in a hereditary manner, and CAS occasionally serves as the appellate court for matters pertaining to certain sports and the public interest.

The Olympic Charter, the FIFA Code of Conduct for football players and coaches, the WADA Anti-Doping Code, and the Anti-Doping Rights Act by WADA are just a few examples of pertinent legislation and regulations that provide a specific sub-discipline approach to the Sports Law milieu.

CONCLUSION

The author concludes that sports law has always existed within legal scenarios around sports. The emergence of sports law can be seen from the employment, taxation and contract related cases. Eventually, issues like stadium safety and safety of spectators arose with time and it required specific rules, regulations and guidelines to set standards for the management and service providers. The issues such as doping and consumption of prohibited substances by athletes to enhance performance were one of the mile stones when creating a legal framework of regulatory bodies and legal proceedings concerning international boundaries. Along with that, there is a hierarchy of power and regulation, for instance, State Governing Regulatory Bodies/Federations have to comply with the standards and guidelines of the National Governing Bodies/Federations. Also, National Governing Bodies have to comply with the International Governing Bodies and there are penalties and sanctions for the avoidance of guidelines and non-compliance of the standards, codes and guidelines. This hierarchy not only keeps a tab on the activities of the governing bodies in hierarchy but it also acts as the appellate authority when it comes to disciplinary proceedings of any sports-person. Although, as the nature of dispute is contractual in nature, the sports-person can take a legal path of civil and criminal action for the breach of contract or any other issue as per the case may be. However, Court of Arbitration for Sports plays a major role in handling these issues. The CAS acts as an appellate authority and remedy of judicial review is provided to the claimants when they have suffered any injustice especially when the matter is regarding the public policy and contains elements of human rights and freedom.

Although, most of the countries have no special legislation on sports law they recognize the existence of sports law through practice, codes and by following the legal jurisprudence. If the author takes the example of India, this country has a National Sports Code and has introduced a bill to give recognition to e-sports as a sports. In a developing country like India, such legal advances are evidence of the awareness, popularity and consumption of sports activities on the largest scale. When the business or any activity happens on the largest scale it requires a rule-book for the damage control and the scenario is the same with Sports Law. The author also finds the emergence of sports law on the footsteps of the Tort law which has no specific legislation but it is defined through the precedents and case laws. The elements of tort were defined by the courts through its judgments where it explained duty of care, civil wrong, negligence and other legal principles. The acceptance of sports law in emerging nations and in the virtual world is a sign of the field’s growth. The Indian government has passed a law regulating e-sports and granting them the status of sports. The actual developments demonstrate that sports law already exists through legislation, norms, practice, and legal jurisprudence in the majority of countries. The author concludes by stating that because everyone is involved in sports in some way, in the future years, the general public will be aware of the specific legal sub-discipline known as sports law, and that sports law is a component of sports culture and as such is always evolving.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

- Legislation

Indian Penal Code

- Cases

Norwegian Committee and Confederation of Sports v. International Olympic Committee (CAS 2002/O/372)

Seymour v Reed (Inspector of Taxes), [1927] AC554, 11TC625,[1927] All ER Rep 294, 137 LT312

Secondary Sources

Books

Sports and the Law

Journals

Entertainment and Sports Law Journal

The International Sports Law Journal

Flaherty v National Greyhound Racing Club Ltd, [2005]

McInnes v Onslow Fane, [1978] 3 All ER 211, [1978] 1 WLR 1520

Enderby Town Football Club Ltd v Football Association Ltd, [1971]

Articles/Websites

Global Corruption Report, 2016

Bleacher Report – http://www.bleacherreport.com

Lexis-UK

http://www.assests.publishing.service.gov.uk

References

Author’s Note: This article is intended for informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice.